1.7.3 - Citizenship and Race Challenged in the Courts

The Asian American Education Project

Grade: 7-10Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies

Number of Lessons/Activities: 4

For most of the first century of the United States’ existence, only free white people could become citizens. Following the Civil War, Black people gained citizenship through the Fourteenth Amendment and the right to naturalize under the Naturalization Act of 1870. However, other non-white people in the U.S., such as the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) community, were left uncertain about what protections and rights extended to them. They turned to the courts to test and expand their rights. In this lesson, students learn about the court cases Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923). Students will compare and contrast these two cases and discuss the role APIDA people played in challenging racist citizenship practices and laws.

How do the court rulings of the Ozawa and Thind cases illustrate the connection between race, citizenship, and discrimination against APIDA people in the early 20th century?

Students will:

- Compare and contrast the court cases of Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923) in order to recognize the role APIDA people played in challenging racist citizenship practices and laws.

Citizenship and Race Challenged in the Courts Essay:

Background:

For most of the first century of the United States’ existence, only free white people could become citizens. Following the Civil War, Black people gained citizenship through the Fourteenth Amendment and the right to

naturalize under the Naturalization Act of 1870. However, other non-white people in the U.S., such as the APIDA community, were left uncertain about what protections and rights extended to them. They turned to the courts to test and expand their rights. In 1886, a Chinese immigrant and laundry owner Lee Yick won the historic case

Yick Wo v. Hopkins in which the

Supreme Court ruled that a law applied

discriminatorily along racial lines was unconstitutional, as all people in the U.S. were entitled to equal protection of the law under the Fourteenth Amendment, regardless of citizenship status. In 1898, the flagship case on birthright citizenship,

Wong Kim Ark v. United States, was decided, after Wong was denied re-entry into the U.S. after a visit to China, claiming that he was a U.S. citizen because he had been born in this country. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court where it ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed citizenship to all those born in the U.S. regardless of their

race or parents’ national origin. These Supreme Court decisions had serious ramifications for not only Asian immigrants, but all Americans, citizens or otherwise, and paved the way for future court challenges by APIDAs.

Essay:

Since the late 1800s, Asian immigrants began facing increasing levels of hostility,

discrimination, and exclusion from the United States. To protect themselves and their communities, Asians and Asian Americans found ways to resist and fight back.

Legal challenges were particularly important for Asian Americans fighting for their rights because many of the obstacles they faced were created by laws rooted in discrimination.

The question of citizenship was addressed in the cases of

Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922) and

United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923). Together, these cases illustrate how the social constructs of

race and whiteness were manipulated to deny

naturalization rights to Asian immigrants.

When the U.S. government attempted to limit citizenship only to whites, Asian Americans quickly moved to prove that they themselves were “white” in one way or another. For example, Takao Ozawa, a Japanese American who had lived in the United States for twenty years, claimed that “whiteness” was a matter of skin color. He argued that his skin was just as pale as white Americans; as such, he wanted to be treated the same as a white person, which meant being granted citizenship. He also emphasized his personal values and beliefs, namely his honesty and industriousness, as a demonstration of being “a true American” at heart. The

Supreme Court unanimously denied Ozawa citizenship, stating explicitly that whiteness only extended to those of “the

Caucasian race.”

Three months later, the Supreme Court changed its own reasoning in order to deny citizenship to Bhagat Singh Thind, an Indian man. Thind was from the northern region of Punjab and moved to the United States as a young man and joined the U.S. Army during World War I. He argued that he should be eligible for naturalization and citizenship because he was of the Caucasian race, as specified by the

Ozawa decision. At the time, people from India were sometimes considered members of the “Caucasian race” by

anthropologists because they came from the area of Caucasus.

In Thind’s case, the Supreme Court found that even though he was Caucasian (meaning from the area of Caucasus), he was not considered white. The Court claimed that whiteness must “be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, synonymous with the word ‘Caucasian’ only as that word is popularly understood.” In other words, there was a “common sense” definition of being white, which meant having white skin, round eyes, narrow noses, and other such features.

The Thind decision had serious consequences for Indian Americans, with many Indian immigrants having their naturalized citizenship revoked. As non-citizens, they were further stripped of their property as well. One tragic example is Vaishno Das Bagai, whose citizenship and store were taken away after the Thind decision, leading him to take his own life.

With these two rulings, the Supreme Court demonstrated it was more concerned about safeguarding white citizenship than maintaining their own line of reasoning or upholding justice for non-white immigrants. For Asian Americans, not having citizenship meant being denied access to full participation in U.S. society. They couldn’t vote for leaders to represent them and own land or property. This marginalization allowed them to be excluded from and harassed by this country.

Bibiliography:

- Anthropologists: experts who study the science of human beings

- Caucasian: of or relating to a race of people native to Europe, North Africa, and southwest Asia in an area called Caucasus; often used to mean whiteness

- Discrimination: the prejudicial treatment of different categories of people on the basis of race, age, or sex

- Legal: of or relating to law

- Naturalization: the admittance of a foreigner to the citizenship of a country

- Race: the idea that the human species is divided into distinct groups on the basis of inherited physical and behavioral differences

- Supreme Court: the highest court in the United States; it consists of nine justices and is the court of final appeal

- Unanimously: with the agreement of all people involved

- Why was it important for Ozawa and Thind to both argue that they were white as opposed to Asian? Do you agree or disagree with their arguments? How so?

- What motivated the Supreme Court to make the rulings they did? Do you agree or disagree with their rulings? How so?

- What are the effects of the Ozawa and Thind cases?

Identification photograph of Wong Kim Ark. In the 1898 case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court recognized his birthright citizenship.

Credit: Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service San Francisco District Office (National Archives, Public Domain Image)

Activity 1: The Importance of Citizenship

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Citizenship unit: Have students review notes about citizenship from the lesson “Citizenship: Introducing the Theme of Citizenship in APIDA History.” Facilitate a discussion about the rights of citizens:

- Ask students to summarize what they have learned about the APIDA community so far.

- Ask students to make a list of rights they think they have as a resident of the United States.

- Inform students that many of these rights are a direct result of citizenship status.

- Inform students that those who are and have been denied access to citizenship, like early Asian immigrants, have fought for citizenship rights.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Be sensitive to the fact that some of your students may not be citizens. Some may be undocumented or permanent residents, etc.

- Inform students that many Americans today have benefitted from birthright citizenship and reveal that they can thank a Chinese American, Wong Kim Ark, for this right:

- Show the “United States v. Wong Kim Ark” video: https://www.pbs.org/video/chinese-exclusion-act-wong-kim-ark-6ynevh/

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits, have students discuss how a Supreme Court ruling has impacted them. Have students talk to a partner and then share responses as a whole group. This activity assumes students are familiar with some major Supreme Court cases. If not, provide some background on landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education.

- Remind students that APIDA communities have faced great discrimination due to the fact that they were seen as perpetual foreigners. Inform them that early Asian immigrants were denied citizenship and all the rights that come with being a citizen, but that some Asian immigrants sought to change the laws and policies by fighting their cases in the court system. Inform students that this lesson will focus on the activism of Takao Ozawa and Bhagat Singh Thind.

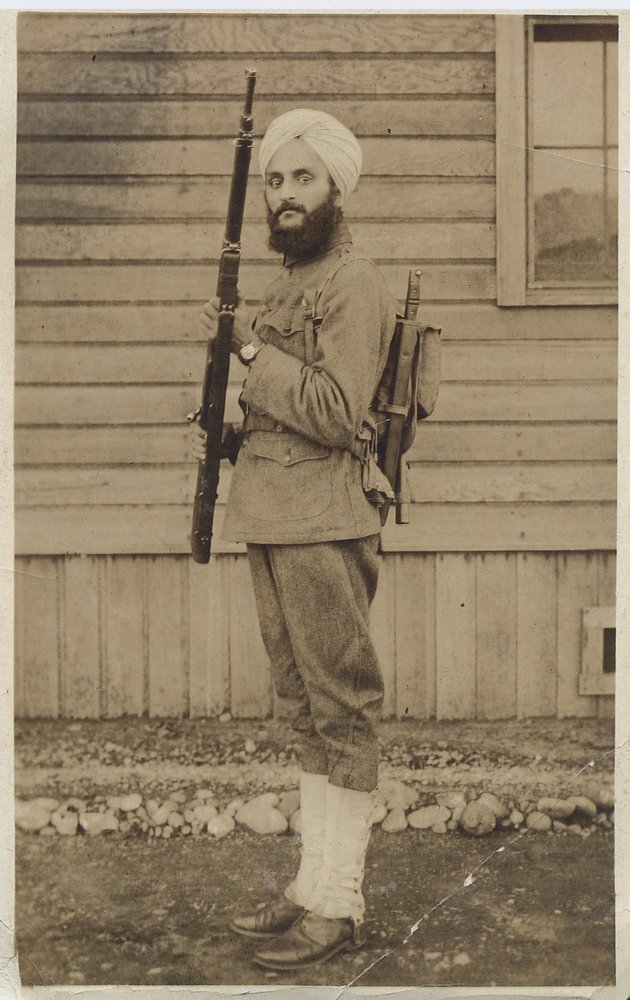

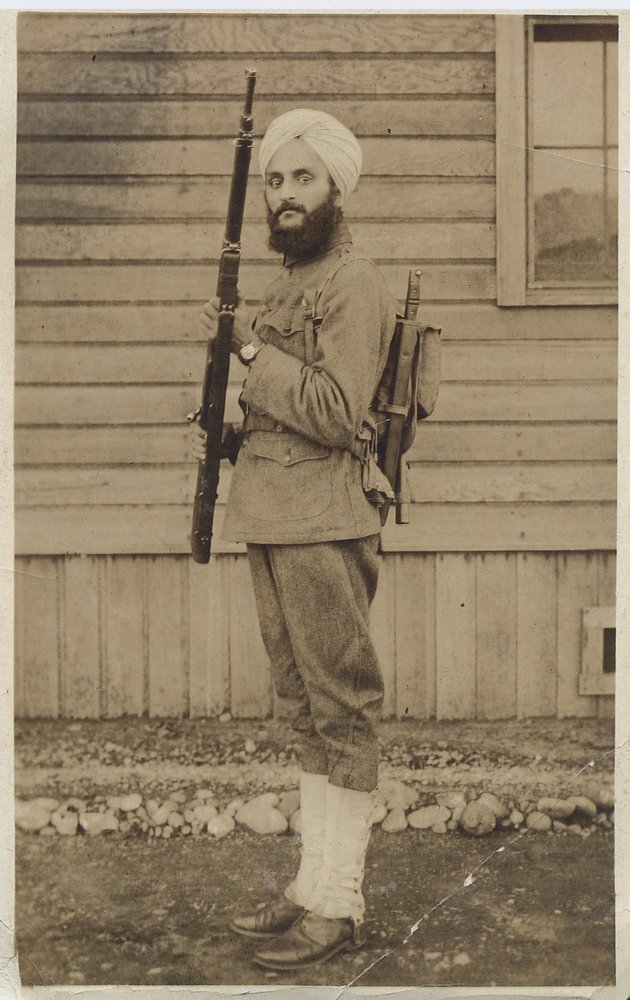

Photograph of Bhagat Singh Thind. The Supreme Court declared Thind ineligible for naturalization in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923).

Credit: Unknown Author, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain Image)

Activity 2: Comparing and Contrasting Citizenship Cases in the Courts

- Have students read the essay about the court cases of Takao Ozawa v. United States and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (see worksheet entitled, “Essay: Citizenship and Race Challenged in the Courts”). Direct students to annotate for similarities and differences. Have students summarize what they learned from the text.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If you have limited classroom time, have students complete the reading as a homework assignment the night before you implement this lesson.

- Facilitate a discussion about the essay using the Discussion Questions.

- Write the following statement on the board: “Race is socially constructed and influenced by cultural norms.”

- Ask students to respond to this statement and discuss how different racial classifications carry social and cultural characteristics that are assigned by society.

- Have students explain how the rulings in the Ozawa and Thind cases support the notion that race is socially constructed.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits and if students need more support, watch the video in The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “Racial Identity and American Citizenship in the Court”: https://asianamericanedu.org/racial-identity-citizenship-in-the-court.html. Before playing the video, provide a content warning to the students that the end of the video mentions suicide.

- Distribute the “Citizenship in the Courts: Compare & Contrast Worksheet.” Have students work in pairs to complete the Venn Diagram by listing similarities in the middle and differences in the outer circles. (See Answer Key)

- Facilitate a class discussion about the court cases using these prompts:

- What are the similarities between the Ozawa and Thind cases? Why are these similarities important?

- What are the differences between the Ozawa and Thind cases? Why are these differences important?

- In what ways did Ozawa and Thind challenge racist citizenship laws and policies? How were their approaches similar and how were they different?

- How did the court treat the Ozawa and Thind cases differently?

- NOTE TO TEACHERS: Comparing and contrasting is an important skill for building comparative thinking. Such thinking is necessary because it helps extract patterns, make connections, and draw conclusions. It also helps identify consistencies and inconsistencies.

The “Old Senate Chamber” in the U.S. Capitol served as the home of the Supreme Court from 1860-1935.

Activity 3: Inconsistencies at the Court

- Distribute the “Inconsistencies at the Court: Ozawa and Thind” worksheet. Direct students to read the text and to pay close attention to the bolded text; encourage them to annotate in the margins. Have students add new information to the Venn Diagram worksheet.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If needed, have students apply the primary source analysis strategy learned in the Citizenship unit lesson entitled “Citizenship and the Right to Public Education” to these excerpts which are primary sources.

- Divide students into five groups. Assign each group a question to discuss and give students about five minutes to discuss as a small group:

- Group 1: How is “white” defined in the Ozawa case? How is “white” defined in the Thind case?

- Group 2: What does the Supreme Court say about the term “Caucasian” in the Ozawa case versus the Thind case?

- Group 3: What basis or authority did the Supreme Court Justices rely on in making their determination of who was “white” in each of the cases?

- Group 4: How does science play a role in the Supreme Court’s reasoning in the Ozawa case and in the Thind case?

- Group 5: How and why did the Supreme Court’s positions change from the Ozawa case to the Thind case?

- Have each group share their response to their assigned question and allow time for other students to respond or add. Instruct each group to answer a question that has not yet been answered until each question is discussed as a class.

- Facilitate a discussion about this text and activities by asking the following prompts:

- What are the consistencies or similarities between the Ozawa and Thind cases?

- What are the inconsistencies or differences between theOzawa and Thind cases?

- Assign students the following task for homework as an assessment: “In one page, explain what the two cases say about citizenship and its relationship to race in the United States in the early 20th century.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Trigger warning as this optional activity speaks of suicide. If time permits, have students complete a primary source analysis (see Citizenship unit lesson entitled “Citizenship and the Right to Public Education”) on Vaishno Das Bagai’s suicide letter which was printed in the March 17, 1928 edition of the San Francisco Examiner (https://www.saada.org/item/20130513-2748). Faced with discrimination, many Indian immigrants left the United States after the Thind case ruling. In 1928, Vaishno Das Bagai committed suicide as a protest against the stripping of his American citizenship.

Activity 4: Comparing to Other Court Cases

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Citizenship unit: Have students discuss the similarities and differences between these two court cases (Ozawa and Thind) and the Tape v. Hurley case in the lesson “Citizenship and the Right to Public Education.” Ask students the following questions:

- How are school segregation and citizenship issues connected?

- By comparing and contrasting all these court cases, what do we learn about the treatment of APIDA communities in the U.S. at this time?

- Inform students that it is important for us to study and compare the activism of those who came before us in order to fight for racial and social justice. Inform students that it is also important to recognize how APIDA communities were active resistors and fought for their rights.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits, ask students: How do you think policymakers, including court judges, use the skill of comparing and contrasting to make decisions?

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Citizenship unit: Inform students that the next lesson will focus on how the constitutional rights of Japanese American were violated during World War II.